Yep, it’s rubber-hose time, folks: a rapid-fire Q&A for those shifty-looking usual suspects ...

What crime novel would you most like to have written?

Murder on the Orient Express by Agatha Christie. It’s a master-class in how to construct a whodunit. The twist ending has largely seeped into popular consciousness, but if you sit down to read the novel again, it’s astonishing to see how deftly Christie sets up and then demolishes the expectations of her readers.

What fictional character would you most like to have been?

Most of my favourite literary icons are tragic figures, great on the page, but you wouldn’t want to be them. I’ll go for Huckleberry Finn, because he knew how to enjoy himself, chewing on a stalk of grass and getting everyone else to do his chores.

Who do you read for guilty pleasures?

I never feel guilty about my pleasures. Catholic Guilt is dead. I do feel a bit cringey when I read Ngaio Marsh though. When she hit her stride, her writing was great, but the overt snobbery, racism and homophobia which occur in so many of her books are appalling today.

Most satisfying writing moment?

When you go off on an unexpected tangent, and it becomes an integral part of the story.

If you could recommend one Irish crime novel, what would it be?

The Book of Evidence by John Banville.

What Irish crime novel would make a great movie?

Uncle Silas by Sheridan Le Fanu. It’s generally considered a late Gothic Romance rather than a crime novel, but I wrote an essay for The Green Book Vol. 4 arguing that it’s an early murder mystery. The mystery wouldn’t confuse modern readers, but a good director could have great fun with the elements of the plot which were to become tropes of the genre. There are multiple suspects and red herrings you could tease out and build on to keep the viewer guessing, and the atmosphere of gloomy horror would be gorgeous on the big screen.

Worst / best thing about being a writer?

The worst thing is the money of course, unless you’re incredibly lucky and can make a living from your writing. Most writers can’t. The best thing is when people tell you how much they enjoy your work.

The pitch for your next book is …?

Sean Vaughan, dwarf detective, solves a series of baffling murders in Trinity College Dublin. It’s Raymond Chandler meets Agatha Christie in a contemporary Dublin setting.

Who are you reading right now?

Tana French. She’s brilliant at creating engaging narrators who draw you into the world of Dublin’s elite Murder Squad. Her novels are very grounded, but she manages to illuminate the horror in everyday life, and the devastating impact of murder on the lives of her characters ring true.

God appears and says you can only write OR read. Which would it be?

I’d say, “Piss off, God! You’re not the boss of me.” Then I’d make a more conducive deal with Satan.

The three best words to describe your own writing are …?

Only bleedin’ massive.

Jarlath Gregory’s THE ORGANISED CRIMINAL is published by Liberties Press.

Showing posts with label John Banville. Show all posts

Showing posts with label John Banville. Show all posts

Sunday, May 10, 2015

Sunday, April 19, 2015

Event: The Franco-Irish Literary Festival

The 16th Franco-Irish Literary Festival takes place from April 24th – 26th, with the theme this year Crime Fiction / Festival du polar:

The events take place in Dublin Castle and at Alliance Française. For all the details on the scheduling, and how to book places, clickety-click here …

“The sustained popularity of the crime novel has long shown that the genre cannot be dismissed as second-class literature. From the early works of Edgar Allan Poe in the 19th century, to the recent TV series The Fall, by way of the French literary collection “Le Masque”, launched in 1927, the crime novel has always moved with the times, and today, in its many different forms, its reach extends across all layer of society. In the 1970s, the slang term “polar” was coined in France. Initially referring to the crime film genre, the term was soon universally adopted to describe the crime novel. The “polar”, this multifaceted and seldom anodyne genre, period-specific and bearing witness to all the power of the pen, is surely every bit as enigmatic and complex as the crimes and mysteries it presents to its readers.”Contributing authors include Stuart Neville, Sinead Crowley, John Banville and Cormac Millar on the Irish side, while France is represented by Hervé Le Corre, Chantal Pelletier, Jean-Bernard Pouy and Didier Daeninckx. The weekend will also incorporate a Crime Fiction Masterclass at the Irish Writers’ Centre hosted by Jean-Bernard Pouy.

The events take place in Dublin Castle and at Alliance Française. For all the details on the scheduling, and how to book places, clickety-click here …

Thursday, March 26, 2015

Review: John Banville on Georges Simenon’s THE BLUE ROOM

John Banville had a fine piece in last weekend’s Irish Times, in which he reviewed Georges Simenon’s THE BLUE ROOM, which has just been republished by Penguin Classics. Sample quote:

“Like all writers he wrote for himself, but before and after writing he had a lively sense of his audience: he wrote for everyone, and anyone can read him, with ease and full understanding. Not for him the prolixity of Joyce or the exquisite nuances of Henry James. This is what Roland Barthes called “writing degree zero”, cool, controlled and throbbing with passion.”For the rest, clickety-click here …

Friday, January 30, 2015

Event: The Guardian Book Club Hosts John Banville on Philip Marlowe

John Banville – aka Benjamin Black, aka Benny Blanco – takes part in a Guardian Book Club discussion on his ‘resurrection’ of Raymond Chandler’s private eye Philip Marlowe in London next Thursday, February 5th. To wit:

“Maybe it was time I forgot about Nico Peterson, and his sister, and the Cahuilla Club, and Clare Cavendish. Clare? The rest would be easy to put out of my mind, but not the black-eyed blonde . . .”For all the details, clickety-click here …

John Banville resurrected Raymond Chandler’s private detective, Philip Marlowe, for his 2014 novel The Black-Eyed Blonde. Set in Los Angeles, in the early 1950s, it begins with a visit from a beautiful, elegant heiress, Clare Cavendish, in search of her former lover. All of the essential noir elements are here - a murder, the powerful family with hidden secrets, the sleezy bars and mean streets of LA, and at its centre Chandler’s wisecracking and world-weary sleuth.

Banville will talk to John Mullan about writing his own Philip Marlowe mystery, the genius of Raymond Chandler and the enduring appeal of one of the most iconic private detectives in crime fiction.

Tuesday, March 18, 2014

“Ya Wanna Do It Here Or Down The Station, Punk?” DA Mishani

Yep, it’s rubber-hose time, folks: a rapid-fire Q&A for those shifty-looking usual suspects ...

What crime novel would you most like to have written?

Probably ROSEANNA, by Swedish authors Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo (1965), the first Martin Beck novel. It taught crime writers that pacey can also be slow and its bitter melancholy is intertwined with the funniest scenes ever written in a crime novel (especially those with American detective Kafka).

What fictional character would you most like to have been?

Any character living permanently in Paris. And since I wouldn’t mind being a real detective, at least for a while, why not Jules Maigret? He’s eating very well, drinking very well, smoking good tobacco, involved in the most interesting cases and still seems so relaxed.

Who do you read for guilty pleasures?

The Classics. Mainly Flaubert or Balzac. Now, for example, I’m reading a beautiful novel by Stefan Zweig and feeling very guilty I’m not reading crime.

Most satisfying writing moment?

Honestly? Writing the words ‘The End’. But also when a character surprises and sometimes even saves you. It happened to me while writing THE MISSING FILE: I thought the novel would end in a very sad way but then a female character I like a lot, Marianka, saved me and offered a new solution that I added to the novel.

If you could recommend one Irish crime novel, what would it be?

Since not many crime novels are translated to Hebrew I'm afraid I don’t know enough Irish crime novels – but I enjoyed immensely Benjamin Black’s CHRISTINE FALLS and THE SILVER SWAN. Obviously Black\Banville is an exceptional writer and I can’t wait to read his THE BLACK-EYED BLONDE.

Worst / best thing about being a writer?

The best thing about being a writer is the fact that everything you do counts as ‘work’. I can watch a crime series on television or read or even just walk for hours and listen to music and still tell myself and others I’m working, and even hard, and that might even be true because who knows, maybe at these exact moments writing is happening inside. The worst thing is that sometimes, no matter what you do and how much you try, writing stays inside and just doesn’t happen elsewhere and then you really feel like you’re doing nothing, staring at your computer screen for hours, while you could (and should) have done something else, real work for instance.

The pitch for your next book is …?

An explosive device is found in a suitcase near a daycare centre in a quiet suburb of Tel Aviv. A few hours later, a threat is received: the suitcase was only the beginning. Tormented by the trauma and failure of his past case, Inspector Avraham Avraham is determined not to make the same mistakes—especially with innocent lives at stake. He may have a break when one of the suspects, a father of two, appears to have gone on the run. Is he the terrorist behind the threat? Or perhaps he’s fleeing a far more terrible crime that no one knows has been committed? (The novel’s name is A POSSIBILITY OF VIOLENCE and it’ll be published in English in July 2014).

Who are you reading right now?

I just finished Ian McEwan’s SWEET TOOTH (what an ending!) after discovering Juan Gabriel Vasquez’ excellent THE SOUND OF THINGS FALLING.

God appears and says you can only write OR read. Which would it be?

I can see my Ego jumping ahead and screaming ‘Write’! But that would have been a very miserable choice. Reading is much more important to my mental health.

THE MISSING FILE by DA Mishani is published by Quercus.

What crime novel would you most like to have written?

Probably ROSEANNA, by Swedish authors Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo (1965), the first Martin Beck novel. It taught crime writers that pacey can also be slow and its bitter melancholy is intertwined with the funniest scenes ever written in a crime novel (especially those with American detective Kafka).

What fictional character would you most like to have been?

Any character living permanently in Paris. And since I wouldn’t mind being a real detective, at least for a while, why not Jules Maigret? He’s eating very well, drinking very well, smoking good tobacco, involved in the most interesting cases and still seems so relaxed.

Who do you read for guilty pleasures?

The Classics. Mainly Flaubert or Balzac. Now, for example, I’m reading a beautiful novel by Stefan Zweig and feeling very guilty I’m not reading crime.

Most satisfying writing moment?

Honestly? Writing the words ‘The End’. But also when a character surprises and sometimes even saves you. It happened to me while writing THE MISSING FILE: I thought the novel would end in a very sad way but then a female character I like a lot, Marianka, saved me and offered a new solution that I added to the novel.

If you could recommend one Irish crime novel, what would it be?

Since not many crime novels are translated to Hebrew I'm afraid I don’t know enough Irish crime novels – but I enjoyed immensely Benjamin Black’s CHRISTINE FALLS and THE SILVER SWAN. Obviously Black\Banville is an exceptional writer and I can’t wait to read his THE BLACK-EYED BLONDE.

Worst / best thing about being a writer?

The best thing about being a writer is the fact that everything you do counts as ‘work’. I can watch a crime series on television or read or even just walk for hours and listen to music and still tell myself and others I’m working, and even hard, and that might even be true because who knows, maybe at these exact moments writing is happening inside. The worst thing is that sometimes, no matter what you do and how much you try, writing stays inside and just doesn’t happen elsewhere and then you really feel like you’re doing nothing, staring at your computer screen for hours, while you could (and should) have done something else, real work for instance.

The pitch for your next book is …?

An explosive device is found in a suitcase near a daycare centre in a quiet suburb of Tel Aviv. A few hours later, a threat is received: the suitcase was only the beginning. Tormented by the trauma and failure of his past case, Inspector Avraham Avraham is determined not to make the same mistakes—especially with innocent lives at stake. He may have a break when one of the suspects, a father of two, appears to have gone on the run. Is he the terrorist behind the threat? Or perhaps he’s fleeing a far more terrible crime that no one knows has been committed? (The novel’s name is A POSSIBILITY OF VIOLENCE and it’ll be published in English in July 2014).

Who are you reading right now?

I just finished Ian McEwan’s SWEET TOOTH (what an ending!) after discovering Juan Gabriel Vasquez’ excellent THE SOUND OF THINGS FALLING.

God appears and says you can only write OR read. Which would it be?

I can see my Ego jumping ahead and screaming ‘Write’! But that would have been a very miserable choice. Reading is much more important to my mental health.

THE MISSING FILE by DA Mishani is published by Quercus.

Wednesday, March 12, 2014

Blonde Ambition

I had a piece published in the Irish Independent last weekend on the new Benjamin Black Philip Marlowe novel, THE BLACK-EYED BLONDE (Mantle), which was very enjoyable to write, not least because the commission required me to write a goodly chunk about Raymond Chandler and Philip Marlowe before getting down to the nitty-gritty of the Benjamin Black novel. I liked the book a lot, by the way, even it’s not a purist’s dream of Chandleresque prose. That piece can be found here.

Meanwhile, John Banville had a very good piece in The Guardian last weekend about his long-standing love affair with the novels of Raymond Chandler, which began at a young age. Here’s a sample:

Meanwhile, John Banville had a very good piece in The Guardian last weekend about his long-standing love affair with the novels of Raymond Chandler, which began at a young age. Here’s a sample:

“The most durable thing in writing is style,” Chandler wrote in a letter to a literary agent in 1945. In this assertion and others like it he was laying claim to his place on Parnassus, if on one of the lower slopes. Flaubert and Joyce complained frequently and loudly of having no choice but to scatter the gold coinage of their prose over the base metal of mere mortal doings, and Chandler too, in his less emphatic, more sardonic, way, sought to set himself among the gods of pure language, pure style.For the rest, clickety-click here …

Like the bard of Bay City, the French and Irish masters of realist fiction frequently professed to care nothing for content and everything for form – and form, of course, was just another word for style. Writing to one of his numerous correspondents, Chandler insisted that “the only writers left who have anything to say are those who write about practically nothing and monkey around with odd ways of doing it”. Out of their grand indifference, however, Flaubert created Emma Bovary and Frédéric Moreau, and Joyce Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus; and Chandler, not to be outdone, gave us Marlowe, the private eye of private eyes, who is among the immortals. – John Banville

Tuesday, March 4, 2014

“Ya Wanna Do It Here Or Down The Station, Punk?” Pat Fitzpatrick

Yep, it’s rubber-hose time, folks: a rapid-fire Q&A for those shifty-looking usual suspects ...

What crime novel would you most like to have written?

Anything by Ed McBain. I picked up one his books in a second-hand book shop in New York because it was a dollar and I liked the cover. Before that I had no interest in crime novels; after that I had little interest in anything else. So McBain is my first love.

What fictional character would you most like to have been?

Philip Kerr’s brilliant creation, Bernie Gunther.

Who do you read for guilty pleasures?

I’d have to plead guilty to John Grisham. But he probably knows a lawyer who can get me off.

Most satisfying writing moment?

The first sentence. It tends to get tricky after that.

If you could recommend one Irish crime novel, what would it be?

THE BOOK OF EVIDENCE. I’m not sure if John Banville meant to it to be read as a crime novel. But that’s how I see it.

What Irish crime novel would make a great movie?

I think THE BOOK OF EVIDENCE would make for a great movie.

Worst / best thing about being a writer?

The worst is the feeling that everything you write could do with a bit of improvement. The best is when someone reads something you wrote and says otherwise.

The pitch for your next book is …?

The pitch is under wraps at the moment because it is a sequel to my current book and I don’t want to give too much away. But here’s a little taster for now:

He didn’t cry out when Fanta McCarthy hammered the long slender nails into his palms. But he knew it was only a matter of time before he told them everything. And then the killing could begin.

Who are you reading right now?

Would you believe EIGHTBALL BOOGIE by a certain Declan Burke? I know that seems like I’m sucking up to my interrogator, but it happens to be true.

God appears and says you can only write OR read. Which would it be?

I’d go looking for a new God, one who isn’t so cruel.

The three best words to describe your own writing are …?

Short, Sharp and Entertaining (I hope.)

KEEP AWAY FROM THOSE FERRARIS is Pat Fitzpatrick’s debut novel.

What crime novel would you most like to have written?

Anything by Ed McBain. I picked up one his books in a second-hand book shop in New York because it was a dollar and I liked the cover. Before that I had no interest in crime novels; after that I had little interest in anything else. So McBain is my first love.

What fictional character would you most like to have been?

Philip Kerr’s brilliant creation, Bernie Gunther.

Who do you read for guilty pleasures?

I’d have to plead guilty to John Grisham. But he probably knows a lawyer who can get me off.

Most satisfying writing moment?

The first sentence. It tends to get tricky after that.

If you could recommend one Irish crime novel, what would it be?

THE BOOK OF EVIDENCE. I’m not sure if John Banville meant to it to be read as a crime novel. But that’s how I see it.

What Irish crime novel would make a great movie?

I think THE BOOK OF EVIDENCE would make for a great movie.

Worst / best thing about being a writer?

The worst is the feeling that everything you write could do with a bit of improvement. The best is when someone reads something you wrote and says otherwise.

The pitch for your next book is …?

The pitch is under wraps at the moment because it is a sequel to my current book and I don’t want to give too much away. But here’s a little taster for now:

He didn’t cry out when Fanta McCarthy hammered the long slender nails into his palms. But he knew it was only a matter of time before he told them everything. And then the killing could begin.

Who are you reading right now?

Would you believe EIGHTBALL BOOGIE by a certain Declan Burke? I know that seems like I’m sucking up to my interrogator, but it happens to be true.

God appears and says you can only write OR read. Which would it be?

I’d go looking for a new God, one who isn’t so cruel.

The three best words to describe your own writing are …?

Short, Sharp and Entertaining (I hope.)

KEEP AWAY FROM THOSE FERRARIS is Pat Fitzpatrick’s debut novel.

Labels:

Ed McBain,

John Banville,

John Grisham,

Keep Away From Those Ferraris,

Pat Fitzpatrick,

Phillip Kerr

Saturday, September 14, 2013

Review: THE CONVICTIONS OF JOHN DELAHUNT by Andrew Hughes

Andrew Hughes’ debut novel opens in 1842, in the Kilmainham Jail cell of the condemned John Delahunt, who has been sentenced to hang for the murder of young Thomas Maguire. Determined to give his side of the story before he dies, Delahunt scribbles a first-person testimony on scraps of paper – although given that Delahunt is an informer for Dublin Castle, and one not above lying to secure a murder conviction for an innocent man, the reader would do well to take Delahunt’s account with a hefty pinch of salt.

Indeed, it’s the self-conscious unreliability of Delahunt as a narrator that gives this charismatic sociopath much of his charm. A historian who has previously published Lives Less Ordinary – Dublin’s Fitzwilliam Square 1998-1922 (Liffey Press, 2011), Andrew Hughes situates this fictionalised account of the historical figure of John Delahunt in a vividly rendered early-Victorian Dublin, but never forgets that his first duty as a novelist is to explore the mystery of character. The structure and tone of the story are reminiscent of John Banville’s The Book of Evidence, and the fictional John Delahunt is both a literary descendant and a spiritual ancestor of Freddie Montgomery. Delahunt is at times a ruthless machine of a man, a cynical misanthropist who feeds on other people’s misery, yet he is capable of great tenderness towards his wife, Helen, and is fully aware of his personal shortcomings, especially in terms of his lack of political or philosophical convictions.

The style, too, is neatly judged. Hughes doesn’t stint on the sights, sounds and smells of Victorian Dublin – a scene where dogs engage in a rat-catching frenzy is particularly toe-curling – but the crisp prose is refreshingly free of stilted, quasi-Victorian phrasing, while the dialogue is delivered in an understated way. In fact, there’s a distinctly modern flavour to the entire story: the deals Delahunt cuts with his Dublin Castle employers, the double-crosses and back-stabbing and ‘confessions’ extracted in subterranean cells, wouldn’t be out of place in a contemporary hardboiled crime novel.

Yet it’s an endearingly old-fashioned novel too, chock-full of the kind of cliff-hangers and reversals of fortune that are to be found in those Victorian stories which were serialised in newspapers and magazines before being bound into novels. These give the story an urgency and tension that might otherwise have been lacking, given that the reader understands from the off that Delahunt must hang. Likewise, the foreboding atmosphere is offset by Delahunt’s bleak sense of humour, which is employed as often as not against himself. It’s a bracing, lurid tale that is as engrossing as it is chilling, and a fascinating glimpse into one of the darker periods in Dublin’s history. – Declan Burke

This review was first published in the Irish Independent.

Indeed, it’s the self-conscious unreliability of Delahunt as a narrator that gives this charismatic sociopath much of his charm. A historian who has previously published Lives Less Ordinary – Dublin’s Fitzwilliam Square 1998-1922 (Liffey Press, 2011), Andrew Hughes situates this fictionalised account of the historical figure of John Delahunt in a vividly rendered early-Victorian Dublin, but never forgets that his first duty as a novelist is to explore the mystery of character. The structure and tone of the story are reminiscent of John Banville’s The Book of Evidence, and the fictional John Delahunt is both a literary descendant and a spiritual ancestor of Freddie Montgomery. Delahunt is at times a ruthless machine of a man, a cynical misanthropist who feeds on other people’s misery, yet he is capable of great tenderness towards his wife, Helen, and is fully aware of his personal shortcomings, especially in terms of his lack of political or philosophical convictions.

The style, too, is neatly judged. Hughes doesn’t stint on the sights, sounds and smells of Victorian Dublin – a scene where dogs engage in a rat-catching frenzy is particularly toe-curling – but the crisp prose is refreshingly free of stilted, quasi-Victorian phrasing, while the dialogue is delivered in an understated way. In fact, there’s a distinctly modern flavour to the entire story: the deals Delahunt cuts with his Dublin Castle employers, the double-crosses and back-stabbing and ‘confessions’ extracted in subterranean cells, wouldn’t be out of place in a contemporary hardboiled crime novel.

Yet it’s an endearingly old-fashioned novel too, chock-full of the kind of cliff-hangers and reversals of fortune that are to be found in those Victorian stories which were serialised in newspapers and magazines before being bound into novels. These give the story an urgency and tension that might otherwise have been lacking, given that the reader understands from the off that Delahunt must hang. Likewise, the foreboding atmosphere is offset by Delahunt’s bleak sense of humour, which is employed as often as not against himself. It’s a bracing, lurid tale that is as engrossing as it is chilling, and a fascinating glimpse into one of the darker periods in Dublin’s history. – Declan Burke

This review was first published in the Irish Independent.

Friday, September 6, 2013

Irish Noir: The Radio Series

‘Irish Noir’ is a new four-part radio series from RTE which begins on Saturday, September 14th. Presented by John Kelly (right), it features contributions ‘from the biggest names in our country’s crime writing scene’, and your humble correspondent. To wit:

Irish Noir is the story of Irish Crime fiction. From its gothic origins, through the fast paced storylines provided by Celtic Tiger excess – and right up to the bleak fictional landscape inspired by Austerity Ireland.To listen in, clickety-click here …

In the last 15 years, Irish crime writing has experienced a renaissance in popularity comparable to the Scandinavian and Scottish crime writing scenes. But before that, Irish crime writing was in the doldrums. Irish Noir is a major new four-part series presented by John Kelly, which will explore why it took so long for this popular genre to get a comfortable footing in this country. To what extent did politics and history play a part? And did the enormous success of Irish literary giants like Joyce and Beckett cloud the ambitions of writers who might have naturally had more hard-boiled aspirations ...? In other words, did we turn our literary noses up at crime fiction?

This will be a must-listen series for all bookworms, featuring contributions from the biggest names in our country’s crime writing scene – John Connolly, John Banville, Tana French, Declan Burke, Declan Hughes, Arlene Hunt, Alex Barclay, and Stuart Neville to name but a few ...

Irish Noir was made in conjunction with the BAI’s Sound and Vision fund. It starts on RTE Radio 1 at 7pm on Saturday September 14th.

Labels:

Alex Barclay,

Arlene Hunt,

Declan Burke,

Declan Hughes,

Irish crime mystery fiction,

John Banville,

John Connolly,

Stuart Neville,

Tana French

Wednesday, June 19, 2013

Between A Rock Guitarist And A Hard Place

There’s a very nice series running over at NPR Books called ‘Crime and the City’, about ‘fictional detectives and the places they live’. The latest destination is Belfast, with NPR being given a tour by ‘the former rock guitarist’ Stuart Neville (right, pictured in No Alibis bookstore). To wit:

While you’re at it, here’s the John Banville / Benjamin Black tour of Dublin, from 2011 …

While Belfast is no longer the burned-out city that it once was, The Troubles still overshadow the city’s story. “We have this kind of strange, contradictory feeling about The Troubles,” Neville says. “We’re ashamed of it, kind of proud of it at the same time.”For the rest, clickety-click here …

While you’re at it, here’s the John Banville / Benjamin Black tour of Dublin, from 2011 …

Labels:

Belfast,

Benjamin Black,

Crime and the City,

Irish crime mystery fiction,

John Banville,

NPR Books,

Stuart Neville

Saturday, June 8, 2013

Black Ops

It took me a couple of books before I began warming to the Benjamin Black novels, but at this point it feels like John Banville has grown into the persona of his crime-writing alter-ego Benny Blanco and – whisper it – may even be enjoying the process. I reviewed the latest Benjamin Black novel, HOLY ORDERS (Mantle), as part of the latest crime fiction column in the Irish Times, which also includes Sara Paretsky’s BREAKDOWN, Benjamin Tammuz’s MINOTAUR and Marco Vichi’s DEATH IN FLORENCE. For more, clickety-click here …

It took me a couple of books before I began warming to the Benjamin Black novels, but at this point it feels like John Banville has grown into the persona of his crime-writing alter-ego Benny Blanco and – whisper it – may even be enjoying the process. I reviewed the latest Benjamin Black novel, HOLY ORDERS (Mantle), as part of the latest crime fiction column in the Irish Times, which also includes Sara Paretsky’s BREAKDOWN, Benjamin Tammuz’s MINOTAUR and Marco Vichi’s DEATH IN FLORENCE. For more, clickety-click here … Meanwhile, if you’re in Dublin city next Wednesday evening, June 12th, John Banville / Benjamin Black will be taking part in a Q&A with Olivia O’Leary at the Smock Alley Theatre. To wit:

Writers at Smock Alley – John Banville as Benjamin Black in conversation with Olivia O’Leary

Venue: The Smock Alley Theatre

Date: Wednesday 12th June – 6pm until 7pm

The Gutter Bookshop are delighted to announce the second event in a new series of author events with their neighbours, the Smock Alley Theatre 1662. Join them in this beautiful and unique theatre to meet bestselling Irish novelist John Banville who will be discussing his new Benjamin Black crime novel Holy Orders with journalist and broadcaster Olivia O’Leary, as well as the new Quirke television series, and the film version of his Booker Prize winning book The Sea. A book signing will take place after the event.

Tickets cost €5 and available from Smock Alley Theatre (01 6770014) or the Gutter Bookshop (01 6799206).

Tuesday, May 28, 2013

Lock Up Your Stained-Glass Windows

It isn’t due until March 2014, unfortunately, but I’m already looking forward to THE BLACK-EYED BLONDE (Henry Holt) by Benjamin Black, aka John Banville, writing in the style of Raymond Chandler about Philip Marlowe. Confused? Well, if Black / Banville adopts Chandler’s haphazard approach to plotting, there’s a very good chance you will be. There’s precious little information available about said plot so far, but as soon as we hear you’ll be the first to know …

It isn’t due until March 2014, unfortunately, but I’m already looking forward to THE BLACK-EYED BLONDE (Henry Holt) by Benjamin Black, aka John Banville, writing in the style of Raymond Chandler about Philip Marlowe. Confused? Well, if Black / Banville adopts Chandler’s haphazard approach to plotting, there’s a very good chance you will be. There’s precious little information available about said plot so far, but as soon as we hear you’ll be the first to know …

Thursday, May 23, 2013

“Publish Or I’m Damned.”

So spake Karlsson, a hero-of-sorts of ABSOLUTE ZERO COOL, a novel published by Liberties Press in 2011. Ironically, given that the tale incorporates a writer’s struggle to get published, Karlsson and AZC had been rejected by a whole slew of publishers – to the point where I was roughly six weeks away from self-publishing the story – before Sean O’Keeffe of Liberties Press stepped in.

So spake Karlsson, a hero-of-sorts of ABSOLUTE ZERO COOL, a novel published by Liberties Press in 2011. Ironically, given that the tale incorporates a writer’s struggle to get published, Karlsson and AZC had been rejected by a whole slew of publishers – to the point where I was roughly six weeks away from self-publishing the story – before Sean O’Keeffe of Liberties Press stepped in. The novel, described as a cross between Raymond Chandler and Flann O’Brien by John Banville, was subsequently shortlisted for the Irish Book Awards in 2011, and won the Goldsboro ‘Last Laugh’ award for comic crime novels at Crimefest in 2012.

So it’s entirely apt, I think, that yours truly, Sean O’Keeffe and Liberties Press’ marketing manager Alice Dawson will be talking about the tricky path to publication at the Dublin Writers Festival later this month. To wit:

Publish and Be FamedFor all the details, clickety-click here.

You’ve slaved away over your keyboard for months, if not years. You’ve researched and imagined, reworked and revised and now, at last, your book is finished. But what happens now? Who guides you down the path to publication? How is your book designed, edited, marketed and promoted? In association with the Dublin Book Festival, Dublin Writers Festival brings together Declan Burke, author of the Harry Rigby Mysteries and one of the most innovative voices in Irish crime fiction, with key personnel from his publishers, Liberties Press, to look at the process of publishing a novel from first idea to the printed page. For anyone interested in unpacking the mysteries of publishing, this event is a must.

Venue: Smock Alley Theatre

Date: Friday May 24th

Time: 1:05 pm

Tickets: €10 / €8

The full programme for the Dublin Writers Festival can be found here.

Monday, January 14, 2013

Nobody Move, This Is A Review: STANDING IN ANOTHER MAN’S GRAVE (Orion) by Ian Rankin

Lee Child recently noted that were he to die, his fans would mourn and quickly move on. Were he to kill off Jack Reacher, on the other hand, the result would be uproar.

It’s an echo of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s experience when he was forced to resurrect Sherlock Holmes after that character’s apparently fatal plunge into the Reichenbach Falls. One of the strengths of the crime / mystery genre is that it encourages the development of a character over a series of novels, to the point where the reader comes to identify more with the hero rather than his or her creator. Thus Max Allan Collins can write ‘new’ Mickey Spillane novels, and John Banville’s alter ego, Benjamin Black, can next year take up the baton from Robert B. Parker in writing about Raymond Chandler’s iconic private eye, Philip Marlowe.

Ian Rankin’s Edinburgh-based Inspector John Rebus is equally iconic. Indeed, he is archetypal in his dour contempt of authority, his solitary nature, his fidelity to old-school policing methods and a fondness for the demon drink.

Ian Rankin didn’t exactly kill off Rebus at the end of Exit Music (2007), the 17th novel in the series and flagged at the time as the final Rebus novel. With his customary fidelity to the realities of Rebus’s experiences, Rankin put Rebus out to pasture, because a police detective of his age operating in Scotland would have reached retirement age.

Rebus requires no melodramatic resurrection for Standing in Another Man’s Grave, then, but it is notable that he is working, in a civilian capacity, in a ‘cold case’ department as the story begins. Approached by a woman whose daughter disappeared many years previously on the A9 motorway, and who is convinced that a recent disappearance of another girl on the same route represents the latest in a series of abductions, Rebus agrees to persuade his former subordinate, Siobhan Clarke, to take the case to her current boss.

Meanwhile, with revised retirement legislation in place, Rebus is angling for a return to professional duties with CID. His reputation should be sufficient to secure his place, but Rebus is under investigation by Malcolm Fox of Edinburgh’s internal affairs department, which is probing his habit of consorting with known criminals, and in particular Rebus’s old nemesis, Ger Cafferty.

With these twin hooks, Rankin draws us into a thematically rich plot which evolves into a meditation on mortality and how best to assess a man’s worth (the novel’s title is adapted from a song by Jackie Leven, a Scottish singer-songwriter with whom Rankin collaborated with in the past, and who died in 2011).

There’s a certain poignancy in the novel’s opening as Rebus, one of the most iconic fictional characters of our generation, fumbles through the ashes of various cold cases, and then proceeds to pursue an investigation largely on his own initiative, all on the basis that his previous dedication to the job has left him solitary and - in his own eyes - irrelevant in his retirement. Painfully aware of his limitations and his diminishing physical capability, Rebus rouses himself - much as he cajoles his battered old Audi into life every morning - for one last tilt at the windmills, convinced that CID’s new and improved policing methods lack the hands-on quality that requires police officers to get said hands dirty, to engage with the criminals and barter away some of your soul, if that’s what it takes to bring a killer to justice.

In that sense the novel is a commentary of sorts on the kind of crime / mystery narrative that has come to dominate popular culture in recent decades, that of the bright, shiny and utterly implausible CSI series and their multitude of spin-offs. Despite the best efforts of his young, social media-friendly colleagues, Rebus remains wedded to the old methods, just as Rankin eschews the easy options, plot-wise, to concentrate on his fascination with the character of Rebus, and how this previously immovable object is contending with the irresistible force of aging and death.

It’s a compelling tale, although fans of the Malcolm Fox stories - the internal affairs man has appeared in two novels published by Rankin subsequent to Rebus’s retirement, The Complaints (2009) and The Impossible Dead (2011) - may be taken aback by Rankin’s portrayal of Fox here. To date an entertainingly flawed character who appreciates that his peers are entitled to consider that his investigations of his colleagues are a treachery of sorts, Fox is here rather one-dimensional, a petty jobsworth determined that Rebus should be exposed as tainted due to his complex relationship with the criminal fraternity.

Perhaps Rankin is burning his bridges with Fox in preparation for more Rebus novels to come. If so, it’s a pity - but then, with Rebus, the ends always justify the means. – Declan Burke

Editor’s Note: The more eagle-eyed Rebus / Rankin fans among you will have spotted that I managed to confuse ‘Audi’ with ‘Saab’ for the purpose of this review. I am currently crouched in a corner wearing a pointy hat.

This review was first published in the Irish Times.

It’s an echo of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s experience when he was forced to resurrect Sherlock Holmes after that character’s apparently fatal plunge into the Reichenbach Falls. One of the strengths of the crime / mystery genre is that it encourages the development of a character over a series of novels, to the point where the reader comes to identify more with the hero rather than his or her creator. Thus Max Allan Collins can write ‘new’ Mickey Spillane novels, and John Banville’s alter ego, Benjamin Black, can next year take up the baton from Robert B. Parker in writing about Raymond Chandler’s iconic private eye, Philip Marlowe.

Ian Rankin’s Edinburgh-based Inspector John Rebus is equally iconic. Indeed, he is archetypal in his dour contempt of authority, his solitary nature, his fidelity to old-school policing methods and a fondness for the demon drink.

Ian Rankin didn’t exactly kill off Rebus at the end of Exit Music (2007), the 17th novel in the series and flagged at the time as the final Rebus novel. With his customary fidelity to the realities of Rebus’s experiences, Rankin put Rebus out to pasture, because a police detective of his age operating in Scotland would have reached retirement age.

Rebus requires no melodramatic resurrection for Standing in Another Man’s Grave, then, but it is notable that he is working, in a civilian capacity, in a ‘cold case’ department as the story begins. Approached by a woman whose daughter disappeared many years previously on the A9 motorway, and who is convinced that a recent disappearance of another girl on the same route represents the latest in a series of abductions, Rebus agrees to persuade his former subordinate, Siobhan Clarke, to take the case to her current boss.

Meanwhile, with revised retirement legislation in place, Rebus is angling for a return to professional duties with CID. His reputation should be sufficient to secure his place, but Rebus is under investigation by Malcolm Fox of Edinburgh’s internal affairs department, which is probing his habit of consorting with known criminals, and in particular Rebus’s old nemesis, Ger Cafferty.

With these twin hooks, Rankin draws us into a thematically rich plot which evolves into a meditation on mortality and how best to assess a man’s worth (the novel’s title is adapted from a song by Jackie Leven, a Scottish singer-songwriter with whom Rankin collaborated with in the past, and who died in 2011).

There’s a certain poignancy in the novel’s opening as Rebus, one of the most iconic fictional characters of our generation, fumbles through the ashes of various cold cases, and then proceeds to pursue an investigation largely on his own initiative, all on the basis that his previous dedication to the job has left him solitary and - in his own eyes - irrelevant in his retirement. Painfully aware of his limitations and his diminishing physical capability, Rebus rouses himself - much as he cajoles his battered old Audi into life every morning - for one last tilt at the windmills, convinced that CID’s new and improved policing methods lack the hands-on quality that requires police officers to get said hands dirty, to engage with the criminals and barter away some of your soul, if that’s what it takes to bring a killer to justice.

In that sense the novel is a commentary of sorts on the kind of crime / mystery narrative that has come to dominate popular culture in recent decades, that of the bright, shiny and utterly implausible CSI series and their multitude of spin-offs. Despite the best efforts of his young, social media-friendly colleagues, Rebus remains wedded to the old methods, just as Rankin eschews the easy options, plot-wise, to concentrate on his fascination with the character of Rebus, and how this previously immovable object is contending with the irresistible force of aging and death.

It’s a compelling tale, although fans of the Malcolm Fox stories - the internal affairs man has appeared in two novels published by Rankin subsequent to Rebus’s retirement, The Complaints (2009) and The Impossible Dead (2011) - may be taken aback by Rankin’s portrayal of Fox here. To date an entertainingly flawed character who appreciates that his peers are entitled to consider that his investigations of his colleagues are a treachery of sorts, Fox is here rather one-dimensional, a petty jobsworth determined that Rebus should be exposed as tainted due to his complex relationship with the criminal fraternity.

Perhaps Rankin is burning his bridges with Fox in preparation for more Rebus novels to come. If so, it’s a pity - but then, with Rebus, the ends always justify the means. – Declan Burke

Editor’s Note: The more eagle-eyed Rebus / Rankin fans among you will have spotted that I managed to confuse ‘Audi’ with ‘Saab’ for the purpose of this review. I am currently crouched in a corner wearing a pointy hat.

This review was first published in the Irish Times.

Tuesday, December 4, 2012

Vote Early, Vote Fowl

You will remember, no doubt, all that hoo-hah about the Irish Book Awards last month, which largely involved dressing up in our best frou-frou frocks (right), air-kissing our way around the RDS, and not winning very much. Boo, etc.

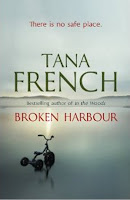

Anyway, one consequence of the IBA Awards is that all the winners from the various categories on the night are now all in contention for the Irish Book of the Year gong. These include John Banville’s ANCIENT LIGHT, Tana French’s BROKEN HARBOUR, Donal Ryan’s THE SPINNING HEART and Maeve Binchy’s A WEEK IN WINTER, but given that Eoin Colfer was the only soul brave enough to wear a cravat on the night of the IBA Awards, we’re going to recommend that you vote for ARTEMIS FOWL: THE LAST GUARDIAN, which was the winner in the senior Young Adult category.

For all the details - it’ll take about ten seconds - clickety-click here …

Anyway, one consequence of the IBA Awards is that all the winners from the various categories on the night are now all in contention for the Irish Book of the Year gong. These include John Banville’s ANCIENT LIGHT, Tana French’s BROKEN HARBOUR, Donal Ryan’s THE SPINNING HEART and Maeve Binchy’s A WEEK IN WINTER, but given that Eoin Colfer was the only soul brave enough to wear a cravat on the night of the IBA Awards, we’re going to recommend that you vote for ARTEMIS FOWL: THE LAST GUARDIAN, which was the winner in the senior Young Adult category.

For all the details - it’ll take about ten seconds - clickety-click here …

Labels:

Artemis Fowl The Last Guardian,

Donal Ryan,

Eoin Colfer,

John Banville,

Maeve Binchy,

Tana French

Thursday, November 22, 2012

The Irish Book Awards: Yep, It’s Third Time Unlucky

Show me a good loser, as Vince Lombardi once said, and I’ll show you a loser. Which is irrefutably true. It’s also true, if we can continue the football analogy, that there’s no shame in being beaten by a better team, and BROKEN HARBOUR by Tana French was a very worthy winner of the Ireland AM Best Crime Novel award at the Irish Book Awards last night.

I’ve said all along this year that BROKEN HARBOUR is a tremendous piece of work, and while it’s always disappointing not to win once you make it onto the shortlist - last night was my third time unlucky at the Irish Book Awards - it was no mean achievement to make it even that far, particularly when you consider some of the very fine novels that didn’t. Anyway, hearty congratulations to Tana French, and sincere commiserations to my fellow nominees Niamh O’Connor, Benjamin Black, Louise Philips and Laurence O’Bryan.

Meanwhile, I was delighted to see Eoin Colfer win in the Young Adult section for the final Artemis Fowl novel, and John Banville win the Best Novel category with ANCIENT LIGHT. For all the Irish Book Award winners, clickety-click here …

I’ve said all along this year that BROKEN HARBOUR is a tremendous piece of work, and while it’s always disappointing not to win once you make it onto the shortlist - last night was my third time unlucky at the Irish Book Awards - it was no mean achievement to make it even that far, particularly when you consider some of the very fine novels that didn’t. Anyway, hearty congratulations to Tana French, and sincere commiserations to my fellow nominees Niamh O’Connor, Benjamin Black, Louise Philips and Laurence O’Bryan.

Meanwhile, I was delighted to see Eoin Colfer win in the Young Adult section for the final Artemis Fowl novel, and John Banville win the Best Novel category with ANCIENT LIGHT. For all the Irish Book Award winners, clickety-click here …

Friday, August 10, 2012

Diamond Dogs

Yet another intriguing Irish crime title emerges in 2012, with the publication of Joe Murphy’s DEAD DOGS (Liberties Press) - although, Liberties Press being my own publisher, I’m reliably informed that DEAD DOGS is not a straightforward crime novel, and may not even be a crime novel at all, but a literary offering with crime fiction elements.

Quoth the blurb elves:

The same issue raised its head a couple of weeks back with Keith Ridgway’s very fine HAWTHORN & CHILD, which features a pair of London-based police detectives but is more a novel about characters involved in crime - victims, investigators, criminals - than it is about the crimes themselves, or their detection and/or consequences.

These are strange but exciting times for the Irish crime novel. One of the best crime titles of the year to date, Tana French’s BROKEN HARBOUR, probably functions best as a novel detailing the personal cost of the Irish economic collapse, and less well as a dedicated police procedural. Only this week, it was announced that John Banville’s alter ego, Benjamin Black, will publish a new Philip Marlowe novel next year in the style of Raymond Chandler.

Meanwhile, authors such as Keith Ridgway and Joe Murphy are offering stories that are bound up in criminal activity, yet shy away from explicitly describing themselves as crime novels. This may be in part a reluctance to be consigned to the crime fiction ghetto, as many people consider it. It may also be a literary reaction to the impossibility of coming to terms with the legal heisting of an entire country by a small number of gamblers and thieves. There’s a kind of schizophrenia abroad than can be loosely summed up as, ‘Yes, a crime took place; yes, it was immoral and unethical; yes, it was fully legal.’

Yet again, I’ll put forward my definition of a crime novel: if you can take out the crime and the novel still works, it’s not a crime novel; if you take out the crime and the story collapses, then it’s a crime novel.

Not that any definition matters, of course. What truly and only matters is whether the book is well written and has something interesting to say. By that mark, and having read the first few pages, DEAD DOGS is a very intriguing prospect. Stay tuned for more …

Quoth the blurb elves:

In rural Wexford, a young teenager is worried about his friend Sean. Sean, you see, has just accidentally killed a pregnant dog and her puppies. Sean isn’t stupid but he sometimes gets a bit confused. When the unnamed narrator brings him to Dr. Thorpe’s house to see about some new medication, they end up watching through the letterbox as Dr Thorpe beats a woman to death. This sharp witted and psychological narrative explores the troubles these teenagers face as they move towards a climax that will tear their worlds asunder.I don’t know about you, but that sounds like a crime narrative to me. Then again, I haven’t had the chance to read the book yet, so I’ll hold fire until such time as I do.

The same issue raised its head a couple of weeks back with Keith Ridgway’s very fine HAWTHORN & CHILD, which features a pair of London-based police detectives but is more a novel about characters involved in crime - victims, investigators, criminals - than it is about the crimes themselves, or their detection and/or consequences.

These are strange but exciting times for the Irish crime novel. One of the best crime titles of the year to date, Tana French’s BROKEN HARBOUR, probably functions best as a novel detailing the personal cost of the Irish economic collapse, and less well as a dedicated police procedural. Only this week, it was announced that John Banville’s alter ego, Benjamin Black, will publish a new Philip Marlowe novel next year in the style of Raymond Chandler.

Meanwhile, authors such as Keith Ridgway and Joe Murphy are offering stories that are bound up in criminal activity, yet shy away from explicitly describing themselves as crime novels. This may be in part a reluctance to be consigned to the crime fiction ghetto, as many people consider it. It may also be a literary reaction to the impossibility of coming to terms with the legal heisting of an entire country by a small number of gamblers and thieves. There’s a kind of schizophrenia abroad than can be loosely summed up as, ‘Yes, a crime took place; yes, it was immoral and unethical; yes, it was fully legal.’

Yet again, I’ll put forward my definition of a crime novel: if you can take out the crime and the novel still works, it’s not a crime novel; if you take out the crime and the story collapses, then it’s a crime novel.

Not that any definition matters, of course. What truly and only matters is whether the book is well written and has something interesting to say. By that mark, and having read the first few pages, DEAD DOGS is a very intriguing prospect. Stay tuned for more …

Labels:

Joe Murphy Dead Dogs,

John Banville,

Keith Ridgway Hawthorn and Child,

Raymond Chandler,

Tana French

Thursday, March 15, 2012

When In Rome, Change Your Name

An Editor Writes: Conor Fitzgerald’s THE NAMESAKE arrived in the post yesterday, which got me all fired up to write a post about it - and then I realised I already had, last November. Bummer. Oh well, I guess I can take the day off now, and go lounge in my gold-plated hammock with the diamond-encrusted hookah …

An Editor Writes: Conor Fitzgerald’s THE NAMESAKE arrived in the post yesterday, which got me all fired up to write a post about it - and then I realised I already had, last November. Bummer. Oh well, I guess I can take the day off now, and go lounge in my gold-plated hammock with the diamond-encrusted hookah … It’s only November, but already 2012 is shaping up to be yet another very fine year in Irish crime writing. I’ve already noted that Adrian McKinty’s latest, THE COLD COLD GROUND will be published in January, with Brian O’Connor’s MENACES to follow in February.

One novel I’m particularly looking forward to is Conor Fitzgerald’s third offering, THE NAMESAKE, which is due in March. Quoth the blurb elves:

When magistrate Matteo Arconti’s namesake, an insurance man from Milan, is found dead outside the court buildings in Piazzo Clodio, it’s a clear warning to the authorities in Rome - a message of defiance and intimidation. Commissioner Alec Blume, interpreting the reference to his other ongoing case - a frustrating one in which he’s so far been unable to pin murder on a mafia boss operating at an untouchable distance in Germany - knows he’s too close to it. Handing control of the investigation to now live-in and not-so-secret partner Caterina Mattiola, Blume takes a back seat. And while Caterina embarks on questioning the Milanese widow, Blume has had an underhand idea of his own to lure the arrogant mafioso out of his hiding place ...I’ve been a fan of Conor Fitzgerald since his first outing, THE DOGS OF ROME, and I thought that the follow-up, THE FATAL TOUCH, was sufficiently good to propel him to the first rank of crime writing, Irish or otherwise - if memory serves, I was moved to compare that novel with John Banville’s THE BOOK OF EVIDENCE. If THE NAMESAKE represents a similar improvement on THE FATAL TOUCH, then God help us all …

Incidentally, it’s interesting that Fitzgerald, who writes under a pseudonym, and is the son of noted Irish poet Seamus Deane, is here playing with notions of identity, and the truth (or otherwise) of names. Post-modern meta-fiction flummery, or simple coincidence? You - yes, YOU! - decide …

Labels:

Adrian McKinty,

Brian O’Connor,

Conor Fitzgerald,

John Banville,

Seamus Deane,

The Namesake,

William Ryan

Sunday, February 12, 2012

Black’s Dark And Banville’s Light

I’m not sure exactly what’s happening with the cover for Benjamin Black’s forthcoming VENGEANCE (August, Henry Holt), or whether we’re looking at UK and US covers, but I know which one I prefer (right). Certainly the ‘bandstand’ cover conjures up the moody, atmospheric tone I associate with Black’s Quirke novels, which are set in 1950s Dublin; the other cover (below) is rather garish, and brings to mind the worst excesses of the kind of slash-‘n’-cash rubbish that seems to be growing increasingly prevalent in crime fiction these days. Or are said novels (or their lurid covers) merely a throwback to the gory, glory days of the pulp novel? YOU decide.

Anyhoo, onto the story itself. VENGEANCE is the fifth in Black’s Quirke series, with the blurb elves wittering thusly:

Anyhoo, onto the story itself. VENGEANCE is the fifth in Black’s Quirke series, with the blurb elves wittering thusly:

A bizarre suicide leads to a scandal and then still more blood, as one of our most brilliant crime novelists reveals a world where money and sex trump everything. It’s a fine day for a sail, and Victor Delahaye, one of Ireland’s most successful businessmen, takes his boat far out to sea. With him is his partner’s son—who becomes the sole witness when Delahaye produces a pistol, points it at his own chest, and fires. This mysterious death immediately engages the attention of Detective Inspector Hackett, who in turn calls upon the services of his sometime partner Quirke, consultant pathologist at the Hospital of the Holy Family. The stakes are high: Delahaye’s prominence in business circles means that Hackett and Quirke must proceed very carefully. Among others, they interview Mona Delahaye, the dead man’s young and very beautiful wife; James and Jonas Delahaye, his identical twin sons; and Jack Clancy, his ambitious, womanizing partner. But then a second death occurs, this one even more shocking than the first, and quickly it becomes apparent that a terrible secret threatens to destroy the lives and reputations of several members of Dublin’s elite.Benjamin Black, as you very probably know, is the alter-ego of John Banville, who also has a novel published later this year. Interestingly - or not, depending on whether you’ve been following the on-off debate about how serious Banville is about writing his crime fiction - he suggested last year, in an interview with The Star’s Mark Egan, that Benjamin Black has influenced the way John Banville writes. To wit:

“Black was able to help Banville,” he says, explaining that the Banville novel he just completed, ANCIENT LIGHT, was improved by his crime fiction.Herewith be the blurb elves:

“Black has got used to doing plots and keeping all that balanced, and Banville has learned some of that from him,” he says.

In ANCIENT LIGHT, Banville revisits his novels ECLIPSE and SHROUD. Narrator Alexander Cleave thinks about the suicide of his daughter Cass and a sexual affair he had as a teenager with a friend’s mother in a small Irish town.

ANCIENT LIGHT is a stunning novel about youth and age, first love and the illusions of memory by one of the finest writers in the English language. An elderly actor remembers his first affair as a young teenage boy in a small town in 1950s Ireland -- the illicit meetings in a rundown cottage outside town; assignations in the back of his lover’s car on a rain-soaked afternoon. And with these memories comes something sharper and much darker -- the more recent recollection of the actor’s own daughter’s suicide only ten years earlier. In John Banville’s dazzling new book is the story of a life rendered brilliantly vivid -- the deluded nature of young love and the terrifying shock of grief. ANCIENT LIGHT is one of John Banville’s finest novels, both utterly pleasurable and devastatingly moving in the same moment.So there you have it. A Black novel AND a Banville novel in the same year? But Mr Publisher-type Ambassador, with these gifts you are surely spoiling us …

Thursday, December 29, 2011

On The Irish Crime Novel and Institutional Cultural Caution

I find myself in a very unusual situation as 2011 draws to a close, because I’ve never before had novels published in consecutive years. Four years separated EIGHTBALL BOOGIE and THE BIG O, and it was another four years before ABSOLUTE ZERO COOL landed on bookshelves last year. And yet, if all goes to plan, my fourth novel should arrive some time around the middle of 2012.

This is, of course, very good news for yours truly, not least because books in consecutive years might create some kind of momentum. Even so, I’m feeling a little bit fraught at the moment. This is partly because there’s still a job of work to be done on the new book, with semi-final revisions due before it goes off to the editor at the end of January, but it’s mainly due to the fact that the new book - formerly known as THE BIG EMPTY, and currently labouring under the working title of SLAUGHTER’S HOUND - is a very different kind of book to AZC.

As all Three Regular Readers will be aware, ABSOLUTE ZERO COOL is a novel that has a little fun with straightforward narrative and conventional tropes, being a story in which an author who bears a very strong resemblance to one Declan Burke is confronted by a character from an abandoned novel, said character being a possibly homicidal hospital porter to demands to be rewritten as a more likeable sociopath, and who promises to make the rewrite worthwhile by blowing up the hospital where he works.

Before it was published, I was worried that AZC might fall between two stools. Those readers who don’t read crime fiction might not have bothered with it, on the basis that it is essentially a crime novel, once you strip away the bells and whistles; and crime fans who prefer their stories told in a straightforward way could well have shrugged and moved on to something more conventional. So I was very pleasantly surprised to find that the book was, for the very great part, pretty well received, and that most reviewers were happy to champion the more offbeat aspects of the story.

Of course, that kind of thing can backfire badly. If I can (immodestly) point you towards the Publishers Weekly review, which is the most recent review AZC has received, the reviewer suggests that, “those looking for a highly intellectual version of Stephen King’s THE DARK HALF will be most satisfied.” Which was nice to hear, although my first instinct was to wonder whether the phrase ‘highly intellectual’ wouldn’t put off more people than it might attract.

The new book, on the other hand, is far more straightforward a story than AZC. It’s a sequel-of-sorts to my first book, EIGHTBALL BOOGIE, and features erstwhile ‘research consultant’ (aka freelance journalist and occasional private eye) Harry Rigby, who has recently been released after serving a term in a prison for the criminally insane. And even if Rigby’s killing of this brother at the end of EIGHTBALL BOOGIE makes him, as one character points out, ‘the least private eye in the business, and Rigby is driving a taxi to earn a living as the novel opens, it is to my mind a private eye story, and proceeds within the parameters of that kind of tale.

So right now I’m a little concerned that those readers who liked ABSOLUTE ZERO COOL for the way it messed around with story and storytelling might be disappointed by the fact that SLAUGHTER’S HOUND has very little interest in meta-narrative et al, and aims instead to tell a hard-boiled tale of fatalistic noir. We shall see.

I’m prompted to wonder about such things by a piece in today’s Irish Times by Mick Heaney, which looks back on the Irish arts world and the way in which, as Heaney says, “2011 felt like a pivotal year, during which Ireland’s cultural landscape started to take on new, as yet unformed, contours.” The piece takes into account film, music, theatre and the visual arts, and has quite a bit to say about literature too. Heaney name-checks some established and new names in Irish literary fiction, before having this to say:

I’m also wondering about the primacy of the elements of that line, and whether crime writers are obliged to first create an entertainment, and then invest that entertainment with ‘contemporary issues and darker themes’; or whether the onus is on the crime author to write about ‘contemporary issues and darker themes’, in the process making them entertaining.

I’m wondering about this because I can write about contemporary issues and dark themes until the cows come home. It’s the making them entertaining bit that keeps me awake at night.

In terms of the bigger picture, such questions are becoming increasingly important, I think. The Irish crime novel has been in the ‘promising’ phase for quite some time now, without ever fully delivering on that promise and crossing over into the realms of fiction to be taken seriously. This may well be because the crime novel is doomed to be considered entertainment first and foremost, and thus irrelevant in terms of what it has to say about the culture and society from which it springs. Just before Christmas, for example, I had a very interesting conversation with a literary editor of one of the Irish Sunday broadsheets, who said that they’d nominated a certain literary title as their book of the year, this on the basis that it was the only novel they’d read that had something to say about modern Ireland, and even though said novel was set in the past. What was implicit in that statement was that crime novels by the likes of Gene Kerrigan, Niamh O’Connor, Adrian McKinty, Colin Bateman, Stuart Neville and Alan Glynn, just to mention some high-profile names, were excluded from ‘book of the year’ consideration because they were crime novelists, even though they all had very pertinent things to say about Ireland in 2011.

Such an attitude, from an ostensibly well-read person who is after all a literary editor, is entirely dispiriting; or would be, if the times weren’t so dramatically a-changing. To quote again from Mick Heaney’s piece:

But if it all looks very placid on the surface, those tectonic plates are shifting. Essentially, there’s a whole new order up for grabs, politically, economically, and in terms of how we speak to ourselves about ourselves.

Writers, to paraphrase the Chinese saying, always live in interesting times, and the crime novel is perfectly positioned right now to colonise the Irish literary landscape over the next few years, to speak to us all about who we are, how we got here and where we are going.

Here’s hoping it rises to the challenge of the new cultural climate, as the current institutional caution is swept away.

This is, of course, very good news for yours truly, not least because books in consecutive years might create some kind of momentum. Even so, I’m feeling a little bit fraught at the moment. This is partly because there’s still a job of work to be done on the new book, with semi-final revisions due before it goes off to the editor at the end of January, but it’s mainly due to the fact that the new book - formerly known as THE BIG EMPTY, and currently labouring under the working title of SLAUGHTER’S HOUND - is a very different kind of book to AZC.

As all Three Regular Readers will be aware, ABSOLUTE ZERO COOL is a novel that has a little fun with straightforward narrative and conventional tropes, being a story in which an author who bears a very strong resemblance to one Declan Burke is confronted by a character from an abandoned novel, said character being a possibly homicidal hospital porter to demands to be rewritten as a more likeable sociopath, and who promises to make the rewrite worthwhile by blowing up the hospital where he works.

Before it was published, I was worried that AZC might fall between two stools. Those readers who don’t read crime fiction might not have bothered with it, on the basis that it is essentially a crime novel, once you strip away the bells and whistles; and crime fans who prefer their stories told in a straightforward way could well have shrugged and moved on to something more conventional. So I was very pleasantly surprised to find that the book was, for the very great part, pretty well received, and that most reviewers were happy to champion the more offbeat aspects of the story.

Of course, that kind of thing can backfire badly. If I can (immodestly) point you towards the Publishers Weekly review, which is the most recent review AZC has received, the reviewer suggests that, “those looking for a highly intellectual version of Stephen King’s THE DARK HALF will be most satisfied.” Which was nice to hear, although my first instinct was to wonder whether the phrase ‘highly intellectual’ wouldn’t put off more people than it might attract.

The new book, on the other hand, is far more straightforward a story than AZC. It’s a sequel-of-sorts to my first book, EIGHTBALL BOOGIE, and features erstwhile ‘research consultant’ (aka freelance journalist and occasional private eye) Harry Rigby, who has recently been released after serving a term in a prison for the criminally insane. And even if Rigby’s killing of this brother at the end of EIGHTBALL BOOGIE makes him, as one character points out, ‘the least private eye in the business, and Rigby is driving a taxi to earn a living as the novel opens, it is to my mind a private eye story, and proceeds within the parameters of that kind of tale.

So right now I’m a little concerned that those readers who liked ABSOLUTE ZERO COOL for the way it messed around with story and storytelling might be disappointed by the fact that SLAUGHTER’S HOUND has very little interest in meta-narrative et al, and aims instead to tell a hard-boiled tale of fatalistic noir. We shall see.

I’m prompted to wonder about such things by a piece in today’s Irish Times by Mick Heaney, which looks back on the Irish arts world and the way in which, as Heaney says, “2011 felt like a pivotal year, during which Ireland’s cultural landscape started to take on new, as yet unformed, contours.” The piece takes into account film, music, theatre and the visual arts, and has quite a bit to say about literature too. Heaney name-checks some established and new names in Irish literary fiction, before having this to say:

“These works suggest Irish literary fiction – the jewel in the crown of Irish writing over the past 20 years – is in a healthy state, but its primacy is quietly being questioned by another, less vaunted, genre.I’m intrigued by the line about ‘how such writers can weave contemporary issues and darker themes while maintaining entertainment value.’ I’ve gone on record here many times to say that the Irish crime novel is important in terms of how it is documenting the upheaval in Irish society, although it’s interesting that of the five writers Heaney mentions by name, three set their novels outside of Ireland, and one sets his stories in 1950s Ireland. Of the batch mentioned above, only Stuart Neville’s STOLEN SOULS was a contemporary Irish tale.

“Crime fiction continued to thrive last year, with writers such as John Connolly and Stuart Neville, and newer arrivals such as William Ryan and Conor Fitzgerald, showing how Irish authors can compete in this huge international market.

“DOWN THESE GREEN STREETS, an anthology of home-grown crime writing edited by novelist Declan Burke, showed how such writers can weave contemporary issues and darker themes while maintaining entertainment value. Such work may not have quite the same highbrow appeal as “serious” fiction, but the fact John Banville’s latest volume, A DEATH IN SUMMER, was published under his crime-writing nom de plume, Benjamin Black, is further indication of how the genre has taken centre stage in the public imagination.”

I’m also wondering about the primacy of the elements of that line, and whether crime writers are obliged to first create an entertainment, and then invest that entertainment with ‘contemporary issues and darker themes’; or whether the onus is on the crime author to write about ‘contemporary issues and darker themes’, in the process making them entertaining.

I’m wondering about this because I can write about contemporary issues and dark themes until the cows come home. It’s the making them entertaining bit that keeps me awake at night.

In terms of the bigger picture, such questions are becoming increasingly important, I think. The Irish crime novel has been in the ‘promising’ phase for quite some time now, without ever fully delivering on that promise and crossing over into the realms of fiction to be taken seriously. This may well be because the crime novel is doomed to be considered entertainment first and foremost, and thus irrelevant in terms of what it has to say about the culture and society from which it springs. Just before Christmas, for example, I had a very interesting conversation with a literary editor of one of the Irish Sunday broadsheets, who said that they’d nominated a certain literary title as their book of the year, this on the basis that it was the only novel they’d read that had something to say about modern Ireland, and even though said novel was set in the past. What was implicit in that statement was that crime novels by the likes of Gene Kerrigan, Niamh O’Connor, Adrian McKinty, Colin Bateman, Stuart Neville and Alan Glynn, just to mention some high-profile names, were excluded from ‘book of the year’ consideration because they were crime novelists, even though they all had very pertinent things to say about Ireland in 2011.

Such an attitude, from an ostensibly well-read person who is after all a literary editor, is entirely dispiriting; or would be, if the times weren’t so dramatically a-changing. To quote again from Mick Heaney’s piece:

“Taken separately, these disparate developments in the literary, theatre, music and visual spheres are exciting; viewed together, they can be seen as the first tectonic shifts in a culture as affected by doubt and upheaval as the wider economy. After all, the current cultural climate was essentially shaped during the extended period of turmoil and decline that ran from the oil shocks of 1973 to the chronic recession of the 1980s, which swept away the institutional cultural caution of before.”Next year will be a tough one for Ireland Inc., and all who sail in her; and so will the following year, and the year after that. Ireland is not Greece, as our politicians are fond of telling our overlords in Brussels and Frankfurt, this because the Irish are accepting their harsh and unfair economic medicine without taking to the streets, going on strike and burning banks and bondholders alike.

But if it all looks very placid on the surface, those tectonic plates are shifting. Essentially, there’s a whole new order up for grabs, politically, economically, and in terms of how we speak to ourselves about ourselves.

Writers, to paraphrase the Chinese saying, always live in interesting times, and the crime novel is perfectly positioned right now to colonise the Irish literary landscape over the next few years, to speak to us all about who we are, how we got here and where we are going.

Here’s hoping it rises to the challenge of the new cultural climate, as the current institutional caution is swept away.

Labels:

Benjamin Black,

Conor Fitzgerald,

Down These Green Streets,

John Banville,

John Connolly,

Mick Heaney,

Stuart Neville,

William Ryan

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Declan Burke has published a number of novels, the most recent of which is ABSOLUTE ZERO COOL. As a journalist and critic, he writes and broadcasts on books and film for a variety of media outlets, including the Irish Times, RTE, the Irish Examiner and the Sunday Independent. He has an unfortunate habit of speaking about himself in the third person. All views expressed here are his own and are very likely to be contrary.